Reversion To The Moral Mean

On Error, Atonement, and the "Right Road."

It’s the 1970s and young behavioral psychologist and future Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman is talking to a group of flight instructors about skill training. He tells them that “rewards for improved performance work better than punishment for mistakes.” All the laboratory experiments with “pigeons, rats, humans, and other animals” prove Kahneman’s point. 1

One of the veteran instructors disagrees. In his long, actual experience, he tells Kahneman, it seems like every time he praises a pilot for an extraordinary maneuver, the next flight is worse. What’s more, if a pilot screws up badly, and the instructor yells at him, the next flight is better.

It’s a classic battle between an ivory tower expert and someone with real world experience. In this case, the academic Kahneman is right!

What the veteran instructor is observing but not really seeing is reversion to the mean. The instructor’s praise and criticism have little to nothing to do with the next flight. Extreme performance, either good or bad, is almost always followed by something less extreme, something closer to the average. The great landings and the slipshod landings are at either end of the classic bell curve. Outliers.

The right road lost

The Kahneman story about reversion to the mean is concerned with observable data points that deviate from what is normal––flight landings, stock market valuations, the time I scored 170 bowling. But what if instead we consider reversion to the mean in the context of something much messier like human behavior?

I was in bed with a cold this week and I read Lily King’s terrific new novel Heart The Lover. There’s a debate that haunts the book: whether flaws in our character lead to inevitable tragedy or whether tragedy is the result of human error, often random, that is capable of being corrected but often is not. Does our fate lie more in the stars or in ourselves? 2

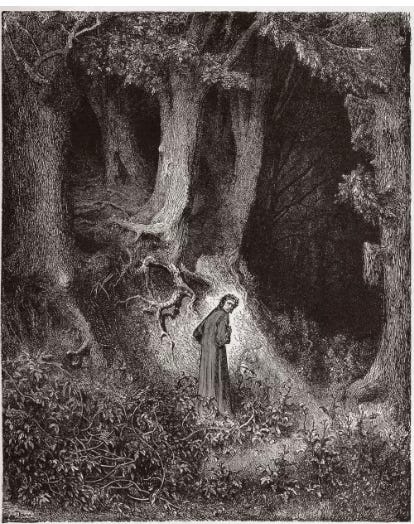

The archaic meaning of the word error is to deviate. The image often used is to wander off the ideal path of correct behavior as in the beginning of Dante’s Inferno

“Midway on our life’s journey, I found myself

In dark woods, the right road lost.”

Atonement and redemption

The pessimist would say that once we stray from the right road, we’re doomed to compound our initial error and drift farther and farther away from our sense of decency until we are hopelessly and irrevocably lost. With our moral compass broken, over time we can become people who are shameful or even monstrous. Certainly, any history book or even any daily newspaper can provide all too many examples of infamous individuals who fit that description.

When I think about my own flaws, however, I notice that the flaws I had in my youth are very different than the flaws I have now at age 63. For example, when I was younger I went through a period of extreme self-doubt. Now, those closest to me will rightfully point out that sometimes I lack sufficient self-doubt, i.e., I can be arrogant.

This evolution in my own flaws gives me cause for optimism. If our flaws are capable of fluctuating, then they are also capable of course correction. But we seldom read in history books and newspapers about famous people who sinned, atoned, and were redeemed.

That’s unfortunate. Arguably, given that we’re all flawed in some way and given that we’re all prone to error from time to time, those who course correct should be our greatest role models.

Profumo

I think of John Profumo, the British MP and cabinet member who in 1963 resigned in disgrace in a very public scandal involving his extra-marital affair, his mishandling of sensitive information, and lying to Parliament.

He died forty-three years later in 2006 after having lived a “life of atonement.” That phrase was in the lede sentence of his obituary in the New York Times, which went on:

“But after his fall, he withdrew permanently from public office, refused to discuss the scandal that had ruined him as a politician and, instead, turned to charitable work among the poor in the hardscrabble East End of London.” 3

No precise moral calculus

The case of John Profumo illustrates that there is no such thing as a precise moral calculus, no way to measure the distance any of us find ourselves from the “right road.” At one moment in life, a person can be thought to be lost forever in the moral wilderness without any hope of a return. Then time passes and things change, and they are held up as a paradigm of atonement and righteous behavior. Wrong and right contend in the same life for supremacy.

It’s no coincidence that I’ve written this essay around the Jewish Days of Awe, ten days ending on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, when we Jews are asked to perform a sort of moral inventory with the goal of a turning toward righteous behavior.

My first reaction to Yom Kippur this year and my first draft of this essay, revealed my flaw of arrogance. It was titled, unironically, Against A Day Of Atonement. And so this essay is itself a turning against that instinct of arrogance, an attempt to revert to a better moral mean.

Question for the comments: Can we ever measure morality and, if so, how?

Thinking Fast and Slow; Daniel Kahnemen.

Heart The Lover by Lily King

King cleverly slips the question into a brief scene of a college classroom debate about the meaning of the Greek word hamartia as Aristotle used it to describe Greek tragic drama. The brilliant student Yash, one of the two main characters in King’s novel gets the better of his professor:

“[The professor] claims that nothing in Greek drama is random and that Greek drama wouldn’t have survived at all without this tragic [character flaw] that they invented. Yash insists that the power and poignancy come from the very randomness itself, the sense that any one of us, not just a good king with a built-in flaw is capable of making a mistake, that we are all vulnerable to tragedy because we are human.”

John Profumo obituary; New York Times; March 2006

To err is human, to forgive is what an alien does!

A thought-provoking question. I can’t see into the hearts of others. I was raised with the injunction: “Judge not, lest ye be judged,” from the Bible of a mother who judged me almost into non-existence. As I’ve aged, I’ve found my moral compass through children. What would my six-year-old neighbor think about me if she knew? Works every time. I rely as well on the memory of my father, still my model of integrity. Then there’s my 22-year-old cat. Her message: I didn’t stick around this long just to watch you f- up. Thank you, David, for the opportunity to sort through this issue in a meaningful, personal way.