My Mother The Absurdist

In 2018, when she was eighty, my mother Jill Roberts became a devotee of Albert Camus and his philosophy of Absurdism––the idea that life has no meaning and never will. Throughout her life my mother had searched for a set of rules to help her make sense of her life, which must have often seemed to her to be profoundly absurd.

She was born in 1938 to parents of great wealth and was expected to become a wife (1957) and a mother (1960, ‘62. 68, ‘70). And that was pretty much all that was expected of her. But she was also born with an intellect and a personality best suited for competition, for curiosity, and for domination. Whether she was born with a fierce temper or whether her temper grew fierce because of her frustrations with her life’s limitations, it’s hard to say.

In her thirties and forties, she became obsessed with becoming an expert bridge player. Anyone serious about bridge will tell you that without obsession, you have no chance to play at the championship level. At those heights, bridge is played with a nuance that rivals the writing of literature or any of the fine arts. My mother played at that championship level.

She gave up bridge, and in her fifties become a devout Orthodox Jew for about a decade. Living an Orthodox life meant she could follow a complete rule book, the Torah. Orthodoxy appealed because it offered a meaning for not only her life but for the universe. It must have made bridge seem small and insignificant.

Then in her sixties my mother found medical philanthropy and that became her career, her vocation, and her passion. She turned her mind and energy to the task of helping people who suffered from inflammatory diseases of the stomach. She read every research paper she could find, ministered to patients, and was determined to make the two centers she founded the best in the world. 1

In my mother’s final two decades––she died in 2020––she lived with great pain, the result of an eating disorder that made her skeletal and vulnerable to broken bones, severe arthritis, and other diseases of inflammation. So, it was natural for her to gravitate toward stoicism.

Her pain was a given. Relief came with drugs that dulled her mind. A rock and a hard place. She’d say these were the cards she’d been dealt and these were the cards she had to play.

Then she discovered Camus and his Absurdism, the idea that there is no meaning to life, and it would be intellectually false not to acknowledge that unpleasant reality.

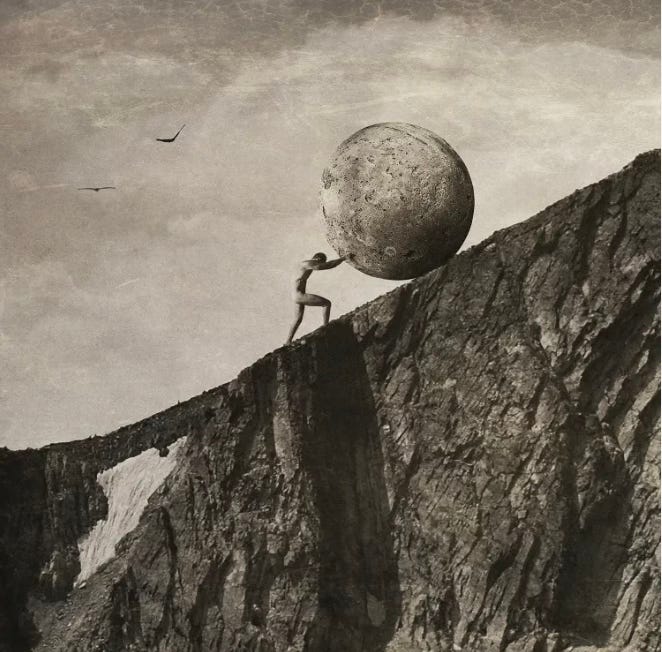

My mother loved Camus’ famous quote about Sisyphus, condemned for eternity by the gods of Ancient Greece to push a boulder up a hill only to see it roll back down. We must, wrote Camus, imagine Sisyphus pushing that boulder back up the hill, imagine him knowing each time that it would roll back down, imagine him knowing that there would never be an end or a respite to his useless labors, and, notwithstanding all that, we must imagine Sisyphus ”happy.”

The Stranger

I thought of my mother and Absurdism because I read Camus’ famous 1942 novel The Stranger this week. I read it because Laura Kennedy had selected it for one of her terrific book group discussions, which I was fortunate enough to participate in just two days ago.

The Stranger is about a young man named Meursault who is radically passive about his life. His passivity leads him into the most grievous of troubles.

The novella famously begins,

“Today, maman died. Or maybe yesterday, I don’t know.” 2

Meursault does not grieve for his mother. He goes to her funeral and sheds no tears. He is impassive because he feels impassive and thinks it’s false to show a feeling he does not possess.

Meursault is passive in almost everything. His girlfriend asks him to marry her, and he agrees. But when she asks him if he loves her, he says no. When she asks whether he would have agreed to marry any other random girl who asked him, he says yes.

Meursault allows various events to unfold around him that ultimately lead to his arrest for shooting a native––they are in French Algeria, circa the late 1930s. His refusal to grieve for his mother or show remorse for the shooting are key to his conviction for murder and his death sentence.

During the book group discussion she led, Laura Kennedy, who holds a PhD in Philosophy, surmised that Camus means to show Meursault as the “bad” kind of Absurdist, a man who in accepting the meaninglessness of life becomes indifferent to everything except immediate sensations. Meursault views his future and his death, whether at 30, 60, or 80, as all the same thing because if life lacks any meaning, then what does anything matter, even one’s death?

In contrast, the “good Absurdist” faces meaninglessness with bravery and decides that whatever they do, they will do well and with grace, even if their life’s task is to roll the same boulder endlessly up a hill.

My mother aspired to be a good Absurdist. In persisting through her pain, she was inspired by and identified with the eternally tortured Sisyphus. When I think of that now, it makes me sad.

My mother’s take on Camus and Absurdism

My mother wrote hundreds of substantive emails to my brothers and me. Below is an excerpt from one of them dated September 18th, 2018 when she was eighty, a short 18 months before she died of a brief and sudden illness.

“Does Camus answer truly the question of the meaning in life? I agree with him that life is absurd. If one accepts that, without retreating into illusion, one can, like Sisyphus, be content… We, like Sisyphus, can focus on whatever is the task at hand and accomplish it even if it has no great meaning. It is the doing that matters, the now, not the future, not the past.”

I haven’t had the courage to go back and read my correspondence with my mother. I disputed much of her philosophy, sometimes with the cruel arrogance of a son trying to show his mother how brilliant he could be.

As well, in that period I considered questions about the meaning of life to be dangerous to my equanimity. I was recovering from a painful and recent time of mental distress that for a while had left me in despair. 3

I wrote the below to my mother in early 2019 (I was 57) :

“I don't see the utility, for me, in thinking about these unanswerable questions. This is what I've tried to explain to you: at this stage of my life, prone to falling into traps of hopelessness, why consider my own insignificance and irrelevance in whatever grand scheme(s) my mind can conjure?”

How absurd that I can’t talk to my mother about Camus now that I’m ready.

Question for the comments: Some people believe we live in a particularly absurd era. What’s your take on Absurdism as a way of confronting life?

The Jill Roberts Center for Inflammatory Bowel Disease at Weill Cornell for patients and The Jill Roberts Institute for Research in Inflammatory Bowel Disease at Weill Cornell to find cures.

My mother would often answer the phones at her Center, and sometimes patients would be first confused and then amazed that they were talking to the woman for whom the Center was named.

Lost in Translation: What the First Line of the Stranger Should Be by Ryan Bloom in The New Yorker; May 11th, 2012. The first lines in French are:

“Aujourd'hui Maman est morte. Ou peut-être hier, je ne sais pas.”

Bloom makes a strong case that Maman is not readily translatable into English. It’s neither Mother nor Mom nor Mommy. As one of our French speaking book group participants said, the French mother-son relationship is culturally specific as is the word Maman.

I still don’t exactly know why I felt so bad during that time. I have hesitated to examine it too closely.

If my sons engaged in substantive, intellectual debate with me, it wouldn’t matter whether they dismissed my ideas as wrong. It’s the engagement that’s an act of love and generosity. You gave her a chance to unspool the meaning of these new ideas—maybe more than you would’ve if you’d placated and agreed. And my guess is that, as your mother, she also saw the tenderness of what you were protecting. I love reading about her. What an exceptional person.

Beautiful homage to your mother, David, may she Rest In Peace.

This is a slight problem with classifying Camus as an absurdist. He was first and foremost an existentialist. Existentialism emerged post-war in France, with its forebearers Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, with its focus on the futility and meaninglessness of life—a notion rampant through Europe after a brutal and devastating war. “Absurdism” was an offshoot. It primarily came from the theater and almost always consisted of dark humor, hence the phrase later coined “Theater of the Absurd.” Its forebearers were Samuel Beckett and Eugene Ionesco. Whereas existentialism’s primary focus was on the futility of existence, the absurdists took that notion to comedic lengths, as in the two tramps waiting endlessly for a myth to arrive in Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot” or Ionesco’s parody of fascism, “Rhinoceros.” Beckett’s play, which is very nearly the same concept as Camus’s “Myth of Sisyphus,” but animated with absurdist comedy. As such, absurdism or “theatre of the absurd” gave existentialism its edge, and for some, a different dimension to the writings of existentialism. Camus’s analogy of Sisyphus had an absurdist twist where it was not originally intended.