Belle Burden's memoir Strangers and the torture of hindsight

Belle Burden’s memoir Strangers is a post-mortem on the sudden rupture of her seemingly idyllic twenty-year marriage. It is marked by the agony of her fight against hindsight bias. The “I should have known’s” and the “how could I have been so stupid’s?” that plagued her and can plague any of us when we look back from the anguish of the present to a serene past and assume, mistakenly, that if we had just been more astute and less naive, then we could have predicted the future. And prevented it.

The destruction of Belle’s twenty-year marriage and the breakup of her three-child family was an earthquake. Her husband “James” abandoned Belle and their children when they were quarantining together on Martha’s Vineyard during the very early days of Covid in March 2020. First came a nighttime phone call from the husband of the woman James was secretly sleeping with. That was followed the next morning by James’ announcement that he was “done” being Belle’s husband and effectively “done” with their children.

When Belle asked him why, James gave no explanation, just an emphasis on the totality and finality of his rejection.

“I thought I was happy but I’m not. I thought I wanted our life but I don’t.”

Belle’s family is famous, glamorous, and old-money. Her parents Amanda and Carter Burden were socialites and a famous “it couple.” Her grandmother was Babe Paley, wife of Bill Paley of CBS fame, and best friend of Truman Capote until Capote betrayed Babe by trumpeting Bill Paley’s affairs.

The wealth and the fame are part of the book’s appeal. Belle brings us inside a type of life that is largely inaccessible. But what propelled my reading was joining Belle in her hunt for the “why” of it all. Also, Belle’s prose carries the unmistakable clarity of the truth as she saw it and felt it.

In the years after the rupture, Belle’s inner voice questions her decisions and the course of her whole life. That voice is fierce and compelling. Her current self argues against that voice. Near the beginning of the book, she writes

“Other couples I knew then, and know now had many more flags, redder flags, and they stayed married.”

But until after I finished the book, I found myself taking the side of Belle’s fierce and critical inner voice. I agreed that Belle had indeed failed to see the red flags of her marriage. And that she had acted impetuously and without judgment about financial matters.

The book effectively recruited me to join Belle’s monstrous inner critic, a critic that was aided and abetted by many factors. There are the thoughtless comments by her friends and acquaintances like her gynecologist who blames Belle for her situation because when Belle gave up her career, she became uninteresting to her husband. There are exogenous reminders such as a deluge of Christmas cards with pictures of families, smiling, loving, and complete. Pictures that Belle tears apart in fury.

But after I finished the book, I understood much better, thanks to Belle, the error of hindsight bias, highlighted by my own hindsight bias about a recent trivial matter.

My trivial example

Eighteen months ago, I bought a mining stock for $5. I sold it last year for $8 because I became nervous about a change in management. Soon after my sale, the commodities the company mined shot straight up in price as did the stock, which went to $20. Even though I’d made money I still felt like an idiot. Irrationally, I’d have felt better if I’d never bought the stock in the first place.

My inner narrative was that I was a fool, a sucker, for having made such an untimely sale. This familiar inner voice is cruel and sadistic. It pounced on me whenever the subject of investments came into view. A newspaper headline, a check-in with the financial markets. Sometimes it caught me totally unaware. It was relentless.

A solution

Then I came across some terrific advice in the Substack newsletter of Dr. Deborah Hall. An excerpt and a link is in the footnote, and I encourage everyone to read it. 1

To summarize Dr. Hall’s insight, the irrational attacks of your inner critic, your “sadistic bully,” will wither if they are exposed to outside light. Just write the ridiculous words down or say them aloud.

So I started to tell my wife Debbie about a terrible mistake I’d made and how I was tormenting myself over it. Debbie assumed I was referring to a grievous bidding error I’d made as her bridge partner in a recent competitive game. That regret she was perfectly happy to have me agonize over so I would not repeat it. 2

But when Debbie heard that my actual, beat-myself-up regret was about the timing of selling a stock, a situation where I could never have expected to know the future direction of the stock as well as unimportant to our lives, she quickly and assuredly confirmed that my self-accusations were absurd.

I immediately felt better and recognized Belle’s memoir as her way of exorcising the bully of her inner voice and inspiring others to do the same.

I found Belle’s husband to be weird, especially about money

It’s easy to make judgments when we’re scrutinizing a relationship from the outside. We’re not in love! Plus we have the advantage of holding in our hands a few hundred carefully written pages detailing the relationship’s entire history.

Nevertheless, I judged.

When I was on the side of Belle’s inner bully, I concluded that the obvious problem with the marriage was that Belle and James had vastly different backgrounds and approaches to money. Perhaps that was my focus because I write about wealth. As well, I can relate to some of Belle’s attitudes about money as a fellow beneficiary of multigenerational wealth. 3

Not surprisingly, I was convinced that James was the weird one about money. His family was briefly wealthy until his father went broke. Because of that, he was parsimonious and careful to a fault.

For example, on their honeymoon when Belle would pay the restaurant check (why is she paying the check when he has a well-paying legal job?) James would get angry that Belle paid without looking, that she didn’t audit the itemized bill. I’m with Belle. I never check the itemized bill. It’s as likely that the restaurant makes an error in our favor as in theirs. And if James really needed to check the itemized bill, let him pay for it!

Or, this:

“[James] asked me to annotate our joint credit card bills, explaining each charge in tiny print.”

Reading that, I’m screaming, Belle, can’t you see how this would never work. The two of you come from such completely different worlds!

Or the sinking feeling I got when I read that James would tell Belle how much money to wire into their joint checking account each month. As if his income didn’t even exist.

And his various machinations over the pre-nup. Dastardly, cheap parvenue without manners!

But then Belle and her inner critic pointed out a habit about James that struck me quite differently.

“[James] didn’t like small talk, and he was always the first to leave a dinner or cocktail party, entirely confident in his right to do so.”

Wait, that’s exactly how my family has described me! And accurately too. I’m a decisive “leaver.” This made me slam the brakes on my judgement.

Why I’m glad I read Strangers

Hemingway defined courage as grace under pressure. In the full telling of her story, Belle is gracious to herself and even to James. She takes us along with her to the healthy conclusion of “Judge not, lest ye be judged.”

As already noted, Strangers is a strong antidote to the poison of hindsight bias.

The book also serves as a warning against allowing the “peak-end rule” to run amuck. The peak-end rule states that for events during any time period, whether an hour of playing tennis or a twenty year marriage, we will overemphasize any peak experience, good or bad, and overemphasize what happens at the end of the experience, whether good or bad.

A highly charged negative emotional peak comes at the end of Belle’s twenty-year marriage. But she is determined not to allow the end to nullify the memory of all the past happy times of their marriage, especially the magic of that first period of falling in love.

Strangers is a master class in humility in accepting that there are certain things about people we can never know. Belle accepts that she will likely never know why James left. People are complex. She also understands herself well enough to realize that she is strong enough not to need to know.

I was having lunch this week with a friend who was reading and enjoying Strangers. My friend said reading the book made her feel a bit like a voyeur. That’s true of any good memoir.

Here is the link to the book’s Amazon page.

Question for the comments: When has your inner critic turned into a sadistic bully?

Excerpt from the post on self-criticism by Dr. Deborah Hall

“what to do

write down

the exact words

the sadistic bully

is leveling against you

once you

do that

you will notice

something surprising

simply

by writing them down

and

exposing the attacks

to the light of day

they begin

to lose their power

why

because

all these accusations

are so absurd

and delusional

that they can

only operate

in the dark.”

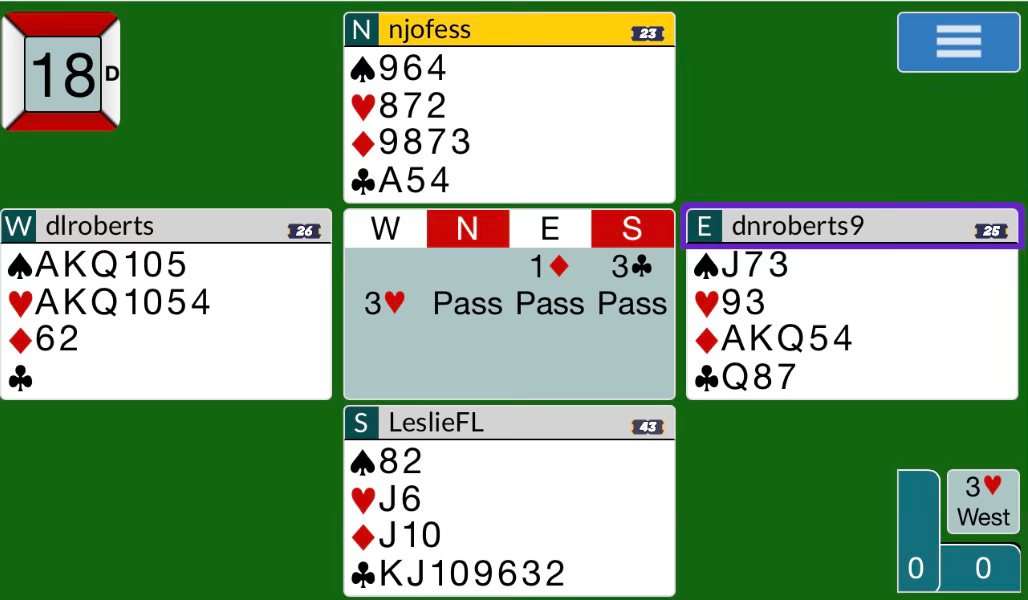

For those who play bridge, my error was that I passed after Debbie had bid a new suit as an overcall. You do not pass when you open a diamond, your opponent bids three clubs and then your partner bids three hearts. Bridge partnerships have been permanently sundered for sins less severe.

Here’s the fateful hand. We could have made a slam. Bridge is a wonderful game! As you play more, you just make different mistakes.

Belle’s family wealth goes back to Cornelius Vanderbilt. Her ancestors became part of the WASP elite. I don’t think I’d ever say that my Jewish family was “old money.” Just doesn’t sound right. The equivalent in the Jewish community would be to trace your ancestors back to sages and great thinkers.

Like me, Belle grew up in Manhattan and she name-checks many of the same places and scenery of the Upper East Side and downtown that are so familiar to me. JG Melon and the Odeon are important landmarks in my own courtship. That made the book even more enjoyable for me to read.

My first thought reading this was for the kids. How their father could just reject them -- or so it seems from the summary. That's cold. As an examination of the inner critic / bully, this is fascinating. My bully (abuser) is most likely an exaggerated version of my critical-but-loving mother. That exercise where you imagine saying even a watered-down version of your inner voice to literally anyone outside yourself - friend or enemy - is illuminating. I love the exercise of writing it down. Reminds me of The Work by Byron Katie. That saved me.

I'm so glad you wrote about this book! I've been talking about it with everyone.

I was sitting in deep judgment of Belle while reading because she did not see the red flags in the way he interacted with her over money, and also the way she handled their financial affairs. The prenup almost did me in! I was like, Belle, you went to Harvard Law and worked at Davis Polk!! You know better. And then she paid no attention to their finances. And then she emptied her trusts to buy homes that she put in both their names. What? It's like a family law hypo on how not to handle your money.

So even though I was "on her side" while reading it, I thought she had been an idiot. Until she started going to dinners with friends of his in attendance, all his male finance and hedge fund buddies and colleagues. They just laughed and talked about how he was playing hard ball. Then it all changed for me.

She may have gone into it with eyes wide shut and stupidly signed one of the dumbest prenups ever. But she did it coming from a place of wanting to trust and love. His behavior, on the other hand (at least in the divorce proceeding), came from a place of something different. Competition, indifference, legal outmaneuvering. And that's when I really came over to her side, just like that!