Imagine There's No Scarcity

I am an example of a wealthy person for whom the “economic problem” of want has been solved in two ways––I’m not troubled by any scarcity, and I have stepped off the hedonic treadmill so that the acquisition of greater wealth is no longer a priority of my lived ambition.

What would a society look like if it achieved enough wealth to free everyone from scarcity.

John Maynard Keynes predicted that this might happen and bring about a disorienting change in what people prioritize and value. Instead of admiring the false gods of wealth and avarice, we would “honour those who can teach us how to pluck the hour and the day virtuously and well.” 1

But “virtuously and well” are ambiguous terms. What do they really mean in the context of a society where there is no economic hardship.

The problem that remains will be what to do with all that free time.

I realize that the “problem” I’m writing about will seem absurd to anyone currently struggling with scarcity. Today there remains the urgent problem of absolute scarcity––insufficiency of food, shelter, childcare, and healthcare.

But there’s also relative scarcity––call it status insecurity––a pain with which I’m familiar and which should not be underestimated even if it can seem irrational and self-inflicted when it’s the affluent who are afflicted by it. Nothing’s good or bad that thinking can’t make it so. 2

And, yes, of course, cue the world’s smallest violin.

Keynes’ predictions

In 1930, as the Great Depression was just beginning to bite, the economist John Maynard Keynes wrote a remarkable essay looking ahead one hundred years. Keynes predicted that the problem of economic scarcity in the developed world would be solved because the standard of living would be eight times higher per capita. Technology advancement would drive productivity increases and then the magic of compounding would do its part––over 100 years, annual gains of just 2.1% produce an eight-fold increase.

At that level of increase, Keynes believed that the new problem, the “permanent problem” would be “how to occupy the leisure, which science and compound interest will have won for [people], to live wisely and agreeably and well.” Another set of terms that resist any precise meaning.

About the economy of the United Staes, however, Keynes was precisely right. America’s real (adjusted for inflation) economic output per capita was about $9,000 in 1930 and is now about $70,000. That’s almost exactly eight times in 95 years. Pretty cool.

Keynes thought this achievement of abundance could rid a society of the worship of wealth accumulation, which he considered a necessary evil until the economic problem of scarcity was solved. Once solved, right about now in 2025, Keynes thought that the “love of money as a possession” would be viewed as a “semi-criminal, semi-pathological propensity,” and that those unfortunates who still suffered from this illness could be “hand[ed] over with a shudder to the specialists in mental disease.”

He did understand, however, that envy and status competition were inherent in the human species so that an insatiable desire for more wealth would not be universally eliminated. But Keynes could not have imagined that the eight-fold increase in wealth would have been shared so unequally or that those at the top would accumulate such massive amounts of individual wealth. Nor could Keynes anticipate how acutely social media has intensified status insecurity.

The dread of the promised land

Keynes wondered whether this new life of abundance might start with a “general nervous breakdown” as people tried to rapidly readjust the habits and worldview “bred into [us] for countless generations.” He goes further and writes of a “…dread. For we have been trained too long to strive and not to enjoy.”

He thought that wealthy people like me, with independent incomes and no need to work, could serve as an “advance guard spying out the promised land.” But when he considered the lives of the wealthy in 1930 Britain––presumably the desiccated aristocracy–– he writes that “they have failed disastrously” to solve the permanent problem of how to live after their economic problem was solved. 3

A perverse silver lining

Keynes was an economist and a realist. He recognized that just as there would always be avarice beyond rational purpose or reason, there would always be some people, dwindling in numbers and need he hoped, who had not yet completely solved their individual economic problems of scarcity.

“…there will be ever larger and larger classes and groups of people from whom problems of economic necessity have been practically removed. The critical difference will be realised when this condition has become so general that the nature of one’s duty to one’s neighbour is changed. For it will remain reasonable to be economically [purposeful] for others after it has ceased to be reasonable for oneself.” 4

There is a perverse silver lining in the continued opportunity to be “economically purposeful for others.” If I imagined a world where no neighbors needed my help, where peace and plenty were universal, what then would happen to my sense of relevance or my sense of virtue?

Under those monstrously placid conditions, my self-esteem would surely plunge. I’d still have my family but my usefulness to them in this strange new world, free from strife, would be scant. I could offer no advice about how to live in such a changed world.

With such a decline in being needed by neighbors and family, I might very well suffer the dread and the nervous breakdown Keynes warned about.

But the reality is that I don’t have to worry about that state of affairs. There is no shortage of problems, no shortage of neighbors who need help. The most vulnerable of our neighbors have become even more vulnerable this year and every sign points to their vulnerability rising in 2026. The world seems anything but placid.

As Auden said of the decade of the 1930s, the time we live in now is “low [and] dishonest.” 5

I doubt myself

Perhaps I have not successfully leapt off that treadmill of material ambition. I have evidence for this doubt––when I’m asleep and my control over my thoughts loses its grip, I often dream of being back at work in a fevered version of my office, trapped in situations I’ve devised to maximize my humiliation and anxiety.

If I were still “in the game,” working like my peers, my status insecurity would be driving and plaguing me often, not just in my dreams. Keynes was right. It’s not so easy to change our ingrained habits. I have suppressed my will to strive. I’ve not silenced it.

Question for the comments: In another one hundred years, if our society again is eight times wealthier per capita than it is now, will Keynes’ prediction finally come through?

All quotes from Keynes’ essay Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren.

From Hamlet : “for there is nothing

either good or bad, but thinking makes it so:”

Keynes may have been thinking about the type of failing aristocratic family depicted by Evelyn Waugh in his 1945 novel Brideshead Revisited.

In a 1959 preface to Brideshead, Waugh expressed surprise that the aristocracy had endured and called his novel “a panegyric preached over an empty coffin.”

Bolding by me.

Auden’s poem September 1, 1939. The first stanza has particular resonance for me:

“I sit in one of the dives

On Fifty-second Street

Uncertain and afraid

As the clever hopes expire

Of a low dishonest decade:

Waves of anger and fear

Circulate over the bright

And darkened lands of the earth,

Obsessing our private lives;

The unmentionable odour of death

Offends the September night.”

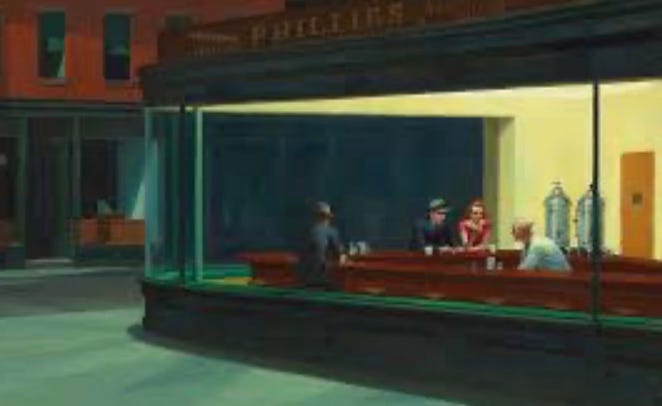

I think of this famous Hopper painting while reading this poem, imagining Auden in this diner, even though it’s not a “dive.”

after careful observation, for 45 years, I have come to see that actual scarcity does not exist in the natural world the way we (have been trained to) experience it as humans. it is an idea that took root. it is an idea that was born of the desire for control, for divide and conquer. those who grow food and soil and save seeds and plant the overflow know that nature provides endlessly and exponentially, if we let her. but then who would be the rulers if there is nothing to rule and the mother births and provides all that we need? what then? well then we would be at the mercy of her, we would have to tend our thoughts and hearts, we would have to see the truth, that we are all equal and one and under the same sun.

Keynes made a rational argument but status insecurity is not rational. I believe it’s human nature to want more and more of what is valued by one’s social community or class. TV shows depict characters like acrabbi and a podcaster living in magazine-worthy homes that the cleaning team has apparently just left. I sometimes wish I had Noah’s kitchen, although Noah is not real. And here on Substack, status anxiety is rampant. Who among us can say with a straight face, “I don’t compare my metrics to anyone else’s?” Not me.