My two cents about my inheritance

My wife Debbie and I needed to decide how or whether we might share our wealth with our adult children. To guide us, we had the good and the bad of my experience having received family money.

This topic was sparked by a few articles that kicked up controversy over parents giving financial support to their adult children. A New York Magazine article focused on the alleged secret shame of adult children receiving parental support. Lindsey Stanberry did a great job in her Substack counter essay showing how such support can be natural and good.

A WSJ article dished about “Trust reveals,” in which supposedly unsuspecting adult heirs are surprised that they have huge trusts coming their way. Allison Tait took that article as a jumping off point in her thoughtful Substack essay about bad and good practices of passing down wealth.

My experience

When I was 18, I came into some money accumulated through annual gifts from both my parents and grandparents in what’s now called a “UTMA”–– Uniform Transfer to Minors Act that liberates funds at either age 18 or 21. Then, at ages 25 and 30, I received more substantial sums in trust when my grandparents died. As well, my mother paid for most of the private school tuition for my children because she wanted to do it and because she could do it free of any tax.

Most of our initial money came from my maternal grandfather who we all called “Ganky” because that’s what his first grandchild, my sister, called him. Ganky was by far the wealthiest person in our family. Born in 1905 in Tulsa, he was a wildly successful oilman in the 1930s and sold out his holdings at the top of one of the oil cycle’s perennial booms.

Growing up, Ganky witnessed a great deal of personal and financial volatility. His older brother was killed by a combination of an oil field accident and the Spanish Flu. His father died of a heart attack in a Tulsa “house of pleasure.” And he saw many families in the tight-knit Jewish community of Tulsa oilmen ruined by lavish spending combined with pressing their luck during the boom years, heedless of the cyclical nature of the oil business.

Once Ganky made his fortune, he was understandably very cautious and conservative about money. For himself and for his family.

Ganky once showed me the photo below, circa 1915, of the black-tie wedding reception for his older sister in a Kansas City hotel. He named the people in the photo, including his ten-year-old self in the back left corner and a few men he said were millionaires at that time but subsequently leveraged and spent their way into bankruptcy. It may have been then that he told me he could have been far wealthier if he’d been willing to take on debt to leverage his investments. But he hated debt!

As the patriarch of the family, Ganky was generous to his two daughters and six grandchildren but he was perpetually frightened that we would squander his money by our extravagance or poor investment choices. Ganky had visibility into all the family accounts, and if our spending looked suspiciously high, he’d complain, usually to my mother.

Only once did Ganky complain directly to me. Debbie and I were just married and we were visiting him in Palm Beach. He told me he needed to speak with me about my spending and asked if I wanted to be alone or with Debbie there. My intuition was that if Debbie was at my side, his lecture would be tempered. And in any case Debbie would want to know precisely what had been said. So Debbie stayed.

The actual “lecture,” turned out to be a profession of love and a gentle request for my assurance, quickly given, that we were monitoring and in control of what we were spending. Ganky’s “lecture”was brief and heartwarming––the twinkle never left his pale blue eyes. It was the sort of shy, hesitating remonstration that the kind and gracious benefactor John Jarndyce from Dickens’ Bleak House might give to his ward.

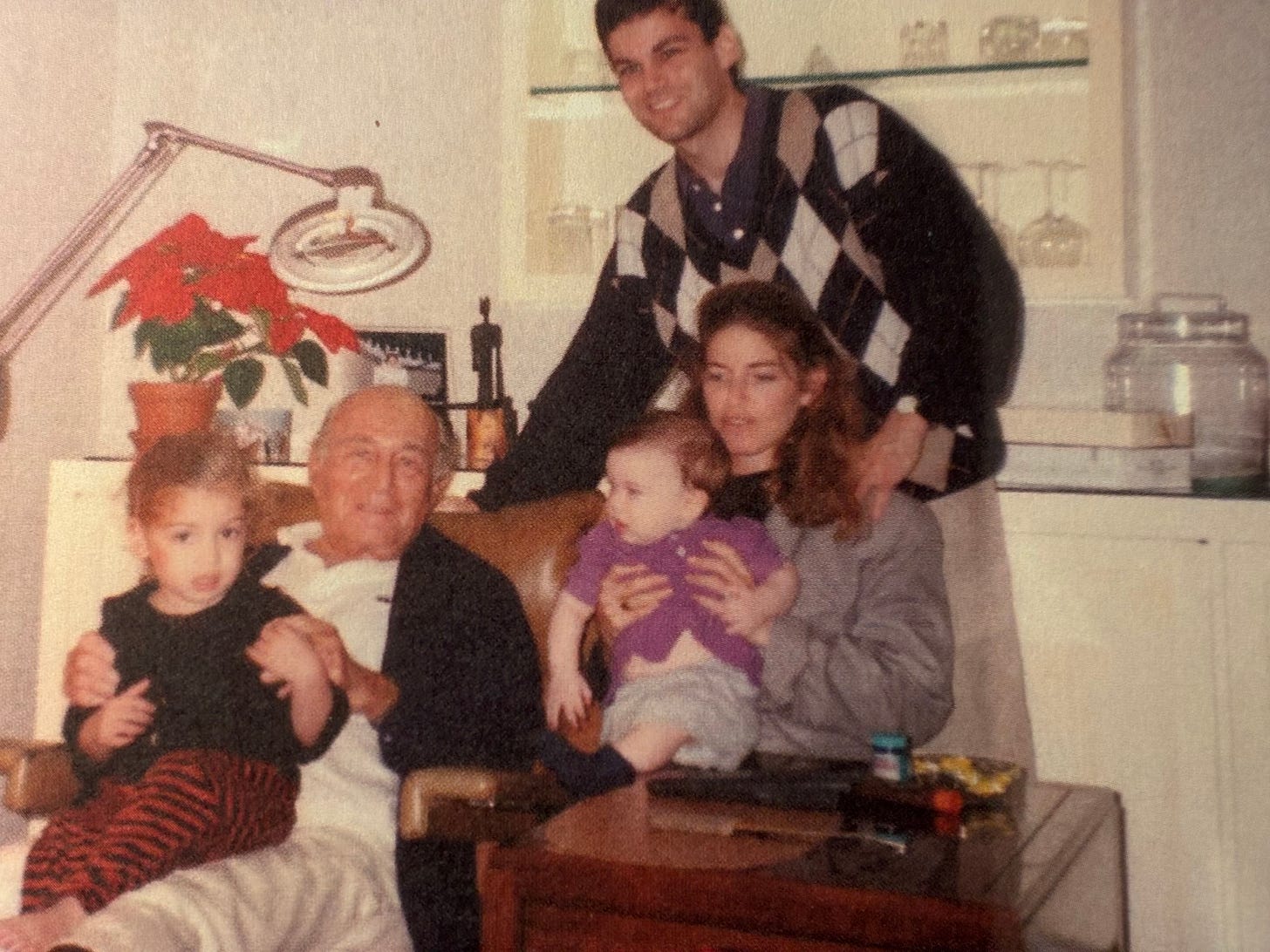

To Debbie and me, Ganky was exactly that––a kind and gracious benefactor. We spent time visiting with him for almost a decade before he died. He was able to meet our first two children. When I told him we had started giving small sums to our children, he replied in his Tulsa twang, “That’s good; you’re building ‘em up.”

The inheritances changed our lives

It turned out that the inheritances I received from Ganky in 1987 (when my grandmother died) and 1992 (when Ganky died) were instrumental to our lives. We were able to have three children and raise them in Manhattan without too much concern over the cost. Although when we bought a six-room apartment on West End Avenue in 1990, the cost of it was very stressful to me. Ganky asked me how much the apartment had cost, and I told him he didn’t want to know.

I joined the asset management firm of Angelo Gordon in 1993 when it was still small. Both my father and Ganky had instilled in me the idea that being an owner was the path to wealth. So, I asked John Angelo and Michael Gordon if I could invest in the firm as a Limited Partner owner. They said yes, although to get “fully invested” with my inheritance money I had to be persistent.

In 2003, when our three children were still young, we set up a trust for them and invested that trust in Angelo Gordon. On the one hand, our family’s investments were highly concentrated. On the other hand it appealed to me that we would sink or swim together.

That investment turned out to be the source of most of our family’s wealth.

Lessons learned

Transparency, education, and talking about money are all good: There was never any effort by my parents or Ganky to hide anything from me. I did receive some suggestions about what to do with wealth––don’t squander and use the money to become an owner. But no one ever spoke to me about the negative feelings that naturally come when you inherit money. It can cast a pall on your achievements and it did for me for quite a while.

As well, it takes effort to make an adult child feel ownership of money that’s given to them. It’s not automatic and you don’t want it to come about because of your own demise.

I previewed this post with our children (in their thirties) to see if they were okay with it. All gave their approval, although one said:

“I think I’ll always be uncomfortable with these revelations. But this [essay] doesn’t really reveal more than has already been revealed so I’m good with [it].”

If you give money, let go of it: Ganky was generous and kindly with me. But his complaints about expenses made my mother feel that the money he gave her was not really hers to use freely. It was only after Ganky died that she felt free to use her money to pursue her passion, which was her medical philanthropy.

Share your good fortune with your heirs when it can be most helpful: I think of Brooke Astor and her son Tony, her only child, who started stealing millions from his mother, beginning when he was in his fifties and she was in her seventies. This continued until his arrest when he was 83 and upon Brooke Astor’s death at 105. Tony Astor was turned in by his son.

Of course that’s an edge case. But the point is if you’re wealthy and don’t share your money, you can create a dynamic where your children may be waiting for you to die so they can “finally get on with their lives.” And why wouldn’t you want to see your children and grandchildren thrive while you’re still around to enjoy seeing them thrive?

I think some wealthy people have a fear that their children really only show them their love and respect because of the money.

Avoid lifestyle whiplash: When you raise your children in an affluent household, they should not expect you to support them in the same manner after they’re out on their own. However, it seems similarly wrong to withhold support you could afford to give and see your children live in a manner drastically different from how they were raised.

Whatever you do, don’t be King Lear: Foolish King Lear abdicates and divides his kingdom between his two sycophantic daughters, Regan and Goneril, experts at false flattery. Lear falls for their overwrought compliments. He disinherits his third daughter Cordelia because she speaks plainly. She merely loves, obeys, and honors Lear as her father.

Once he’s given everything away, Lear is betrayed by Regan and Goneril. Lear feels the bite of their treachery as “sharper than a serpent’s tooth.” Cordelia flees to France. Not only has Lear given away too much too soon, he’s made the blunder of treating his three daughters unequally. A civil war breaks out in which all three of Lear’s daughters die. Lear dies in grief.

You have to have a very good reason to treat your children differently when it comes to providing them with financial and any other support.

The ethical tension

I’ve written repeatedly that excessive economic inequality in America is a problem. Yet if I take steps to ensure the financial prosperity of my children I’m contributing to that inequality. My attempt to soften the edges of this conflict is to make giving to others a significant use of my resources. Still, the conflict remains.

The parental urge to protect and provide for my children is stronger in me than any remorse over contributing to an unjust and dangerous societal condition. Sometimes, there’s no way to square the circle, and the best we can do is to acknowledge that we can’t.

Question for the comments: What say you from experience and observation about this “touchy” subject?

If you find this subject interesting, I recommend Lindsey Stanberry’s and Allison Tait’s Substack newsletters. I benefitted from their thoughts and their posts on this issue.

Lindsey’s post is Why do we get so mad about parents supporting their adult children?

Allison’s post is Planning the Perfect Trust Reveal.

I also recommend and am grateful for the thoughts of Michelle Teheux who writes about wealth inequality at Untrickled by Michelle Teheux.

Finally, check out this clip from King Lear, literature’s all-time worst estate planner.

David, thanks for linking Lindsey’s counter-essay. I was especially struck by the linguistic implications of how we talk about money, for example “sharing” versus “giving.” Those terms carry collective versus individual connotations that can meaningfully shape how children understand family resources and, later, their broader ideologies around money.

This framing can have positive effects not only in families with wealth but also in those without it. In many immigrant households, for example, one sibling might work and then share resources according to need with other family members. This is not to romanticize those systems, which can come with their own forms of obligation or emotional complexity, but the expectations and logics around money are at least visible rather than obscured. By contrast, when parents use money primarily as leverage, as a dangling carrot to reward “good” behavior or punish “bad,” they do not meaningfully teach a work ethic or the value of a dollar. They teach children to orient themselves toward money as the ultimate arbiter of worth—to value the dollar above all else.

I also think it is worth examining a recurring pattern that often appears in wealthy and market-oriented family cultures, though it is by no means exclusive to them. In these environments, children can come to feel entitled to their parents’ wealth, as if the arbitrary luck of birth were a fair measure of who “deserves” what, an inherently unstable and morally loaded concept. Despite not earning the money themselves, they are often quick to frame their parents’ success as evidence that such outcomes are broadly replicable in North America, a narrative that conveniently minimizes their own good fortune. This logic leaves little room for the reality that many people work hard and still do not make money, or for the central role luck plays in shaping economic outcomes.

Acknowledging the arbitrariness of wealth does not guarantee generosity or humility, but it tends to make those qualities more possible. It can also give children real agency. Transparency about the presence or absence of family wealth, at the appropriate time, is not the same as granting unrestricted access to it. Rather, it allows children to evaluate risk, ambition, and failure more honestly, and to make decisions about their lives without relying on falsified modes of motivation. For example, a child who knows that some family wealth will eventually be shared with them may feel more able to pursue the arts, while someone who believes scarcity is absolute may choose a more predictably lucrative path instead. That tradeoff is reasonable when scarcity is real. The problem arises when families manufacture scarcity out of fear of spoiling their children, only to produce adults who later realize they could have pursued their passions more fiercely without financial ruin.

I also appreciate your honesty about the parental urge to protect one’s children being stronger than any remorse over contributing to an unjust or unstable social order. That impulse is deeply human. Many parents share this exact urge but, through sheer luck of the draw, cannot afford the same protections. No one chooses the family they are born into. Taking this seriously pushes the conversation beyond individual parenting choices and toward the systems we collectively tolerate.

Always appreciate your thoughtfulness, candor, and contributions to these conversations!

Yeah, I relate. My grandfather was Milt E. Mohr (Google him), CEO of Quotron and many other companies over the decades between the 1950s-80s. He handed wealth down to my dad who handed it down to me. I've been lucky on that front but I never got one big lump sum. More like help over the years without expecting repayment. It's definitely a privilege. I was a really bad alcoholic and bad spender throughout my twenties but got sober before 30 and grew up/matured. I can see how it could potentially be harmful to gift money to your kids. And I see the potential benefits. Complex. Pros n cons. I will say that growing up with a lot of blue collar friends I was always the odd kid out, the 'rich kid.' And in my twenties people often dismissed my trauma because I 'had money.' And if you 'have money' you can't really have serious problems.