Charlie Kirk, Collective Blame, And The Crucible

The assassination of Charlie Kirk was a tragedy and any celebration of it grotesque. Kirk was an extremely effective, energetic, and prominent recruiter of young voters for Trump and of young adherents to the MAGA movement. He was thirty-one years old, the same age as my younger son.

I’ve been alarmed by the instinct for assigning collective blame for the assassination coming from all sides, some surprising. Derek Thompson, a moderate writer I admire, used collective blame in a very broad and seemingly innocuous sense.

“This assassination was drenched in the digital consciousness that is co-created by you and me and everyone we know and everyone we don’t know. We cannot stop each lightning bolt, and yet we are the weather.” 1

One could infer from Derek’s comment that all users of social media share some blame for Charlie Kirk’s assassination. Similarly, a phrase I’ve read and heard often is “We have to be better.” Who is this “we?”

I profoundly disagree with all of this. I can only be responsible for my actions or inactions, no one else’s. Collective blame in any form is never innocuous, because it’s a concept so often weaponized to harm entire communities, usually those whose beliefs, ethnicities, or religions differ from whoever is in power.

Perhaps as a Jew I’m especially sensitive because I know that “It’s the Jews’ fault” is a common historical refrain often followed by violent persecution. Collective blame is at the root of every genocide. Collective blame is a favorite tool of every authoritarian regime.

The Crucible

Arthur Miller’s response to the 1950s McCarthy “Red Scare” was his play The Crucible about the 1692 Salem witch trials. The play premiered in 1953 when Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) were conducting “witch hunts” for suspected communists. The committees used their powers to rampage through many American institutions, ruining careers and lives.

The similarities between McCarthyism and Salem were unmistakable. Both involved fevers of persecution based on spectral, specious evidence. Both offered the victims of persecution the opportunity to cleanse themselves by publicly admitting their sins and giving up the names of others who had consorted with the Devil or sympathized with communism.

The similarity that strikes me most, however, is the dangerous use of collective blame, the idea that the existence of “sin” in a community, whether in a small village or in Hollywood or in the State Department, meant that the entire community is sinful until and unless all sinners confess or are eliminated.

A vulnerable community gripped by fear

It’s important to understand the role of fear when collective responsibility turns ugly and becomes collective blame.

Miller describes Salem in 1692 as

“…a few small-windowed, dark houses snuggling against the Massachusetts winter…The edge of the wilderness was close by…dark and threatening, over their shoulders night and day, for out of [that dark forest] Indian tribes marauded…” 2

The Puritans of Salem Village likely survived their hardships because they all had to obey the same strict, theocratic code binding them together tightly against the terrors of the wilderness. One of those terrors was the devil. In 1692, belief in the devil and in witchcraft was widespread, perhaps universal. If witchcraft wasn’t real, then why would the Bible have proscribed it––“Thou shall not suffer a witch to live.” To deny the existence of witchcraft or of Satan was to deny the authority of the Bible. 3

So, the witch trials can be seen as a tragic, panicked purification rite run amok in a community that saw itself in perpetual physical and spiritual danger. The executed “witches” were those who were accused but would not confess their sins publicly and name others.

The hero of Miller’s The Crucible is John Procter who is accused of witchcraft by the teenage girl with whom he had an affair. In Miller’s telling, Proctor redeems himself by going to the gallows rather than naming others explicitly or implicitly. For his refusal, he dies but keeps his “good name.” 4

The Soviet conspiracy

America in 1953 had its own perceived vulnerability. Communists in the homeland were perceived as real of a threat to Americans then as witches were to the Salem villagers in 1692. The large number of American Communist Party members and sympathizers of the 1930s had dwindled by 1953, but not to nothing. And it was true that the USSR had communist spies in America.

Instead of the dark, foreboding forest at Salem’s edge, there was the map of the world––the vast land masses of Russia, Eastern Europe, and China already colored “Communist Red” and threatening to spread further like a disease.

The external threat from the USSR was real and needed to be “contained,” a strategy developed by George F. Kennan who first set forth “Containment” in his enormously influential “Long Telegram” of 1946. The fear of the external Soviet threat was heightened by their acquisition of nuclear weapons circa 1950. 5

But the real external Soviet threat was conflated with an imagined Soviet conspiracy within the United States involving vast numbers of supposedly disloyal Americans. To the rabid communist hunters in Congress, a single unexposed communist in a nation of hundreds of millions was still one communist too many. And a refusal to name names was to deny the existence of the vast Soviet conspiracy that most Americans were certain existed. Any communists in the State Department or in Hollywood meant that the State Department and Hollywood were infested with communists. Every one of them needed to be rooted out. Like the Salem witch trials, the “Red Scare” of the 1950s was an exercise in purification as a reaction to fear.

A point of moral reference

In 1996, forty-three years after The Crucible was first performed, Arthur Miller wrote a remarkable essay in the New Yorker titled Why I Wrote The Crucible. It’s well worth quoting from because it seems relevant to America in 2025.

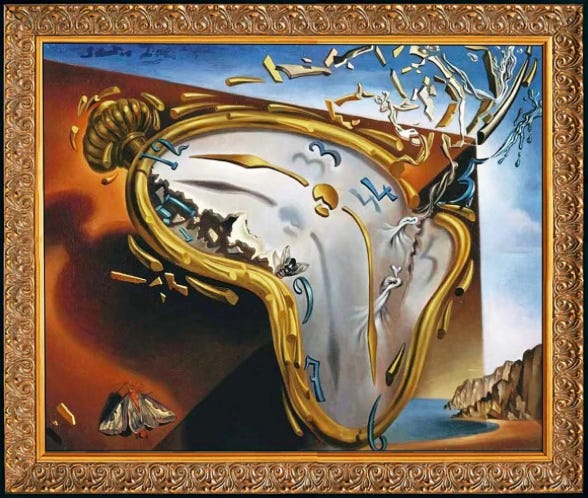

“The Crucible was an act of desperation…In any play, however trivial, there has to be a still point of moral reference against which to gauge the action. In our lives, in the late nineteen-forties and early nineteen-fifties, no such point existed anymore…Gradually, all the old political and moral reality had melted like a Dali watch…our thought processes were becoming so magical, so paranoid, that to imagine writing a play about this environment was like trying to pick one’s teeth with a ball of wool;” 6

Miller had the courage of his convictions. He was not surprised at the hostility to his pointedly political play. It made him a target, and in 1956, he was summoned before the HUAC, which held him in contempt for refusing to name names.

Miller was a young man of 38 when he wrote The Crucible. In his New Yorker essay forty years later, he provides perspective looking back.

“What terrifies one generation is likely to bring only a puzzled smile to the next.…films of Senator Joseph McCarthy are rather unsettling—if you remember the fear he once spread. Buzzing his truculent sidewalk brawler’s snarl through the hairs in his nose, squinting through his cat’s eyes and sneering like a villain, he comes across now as nearly comical, a self-aware performer keeping a straight face as he does his juicy threat-shtick.” 7

Summing up

The fevered persecution of witches in 1692 Salem burned out relatively quickly, lasting a year. Twenty people were executed. Five died in jail. Two dogs were shot. 8

The effects of McCarthy’s Red Scare are harder to quantify. A charlatan like Joe McCarthy can do a lot of lasting damage even if in hindsight we can see what a coarse buffoon he was. The panic over a vast Soviet conspiracy lasted for many years and destroyed many lives. Even when the panic died down, the political lesson learned by the Democratic party was to avoid, at any cost, appearing “weak” on communism. That “lesson” contributed to the decisions taken to intervene and escalate in Vietnam.

As for our current political moment, the rhetoric of collective blame for Charlie Kirk’s murder and the threats of retribution echo McCarthyism. We are told by the most senior leaders of the administration that “every resource” of the Federal Government will be used against an undefined “vast terror network” of the Left.9

It’s difficult right now for me to imagine, as Arthur Miller wrote of McCarthy, that a future generation will look back on the Trump era with “puzzled smiles.”

But perhaps that’s always how one feels when living through a time of history that frightens. Although I have no basis of comparison because I’ve never had similar feelings any other time in my life.

Of course, I know this time is not frightening to everyone. In fact, it probably feels exhilarating rather than frightening to about half of the country.

But it’s frightening to me because I see

“…the old political and moral reality [melting] like a Dali watch.” 10

Question for the comments: Are you frightened? If not, I want to know why because I’d much rather not be frightened.

Clip below from the movie version of The Crucible. Paul Scofield as the Lead Judge.

The Crucible with an introduction by Christopher Bigsby; 1995; Penguin Books

From the introduction by Christopher Bigsby:

“Miller observed in his notebook, ‘Very important. To say there be no witches is to invite charge of trying to conceal the conspiracy and to discredit the highest authorities who alone can save the community!”

Tagging Jillian Hess whose Substack Noted features and analyzes excerpts of the notes of great artists and writers. I’m a fan!

The recent Broadway play John Proctor Is the Villain is a brilliant riff on The Crucible, set in a modern day high school classroom where the students are studying Miller’s play. John Proctor had a limited run and was a hit. If it returns and you get the chance to see it, I recommend it. The play is being adapted into a movie.

The Long Telegram by George F. Kennan is highly recommended reading for those interested in the Cold War and in Russia. I also recommend Kennan’s article, A Fateful Error from 1997 warning about the negative consequences of NATO expansion to Russia’s borders.

Why I Wrote “The Crucible” Arthur Miller in The New Yorker October 13th, 1996.

Ibid.

Numbers of victims taken from the introduction to The Crucible by Cristopher Bigsby referenced above.

The quote is from The New Yorker article referenced above.

I’m Australian and I’m frightened. To see a country change so rapidly is terrifying. I can see similar elements here in Australia. Sigh. Let’s hope that ‘this too shall pass’.

I am extremely apprehensive. I don’t know whether it is fear. I find myself staring into the eyes of ancient enemies and knowing what I am seeing. I am gearing up to deal. My father fought Nazis. I hope his courage is inherited.